|

RESEARCH

|

||||

SPECIATION AND ADAPTATION TO NOVEL ENVIRONMENTSThe process of speciation, despite its overwhelming role in the origins of biodiversity, remains poorly understood. For sexually reproducing organisms defined by the Biological Species Concept, we still are unclear regarding many basic questions: How often does sympatric rather than allopatric speciation occur? What are the relative roles of sexual behavior, postcopulatory-prezygotic incompatibilities, and postzygotic problems such as hybrid sterility and inviability in reproductive isolation? Is there a particular degree of genetic differentiation associated with the appearance of one or more of the categories of isolating mechanisms? What is the role of ecological adaptations in reproductive isolation? |

Cardón cactus at Bahia Concepión |

|||

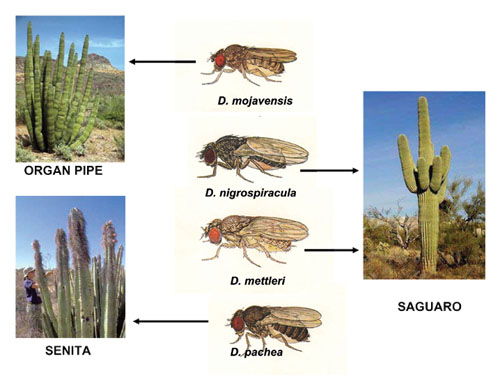

In order to address these issues in a comprehensive framework, we need to utilize a group of organisms that not only is ecologically defined, but one for which we can employ modern molecular approaches. One group of organisms, the cactus breeding Drosophila (fruit flies) of the Sonoran Desert of North America, are ideally suited to studies of adaptation and speciation. Four species of Drosophila are endemic to the Sonoran Desert of North America: D. nigrospiracula, D. mojavensis, D. mettleri, and D. pachea. Each uses the necrotic tissue of a different columnar cactus species as a feeding and breeding site, with the exception of D. mettleri, which breeds in soil beneath a necrotic cactus that has been soaked with necrotic juice. In order to address these issues in a comprehensive framework, we need to utilize a group of organisms that not only is ecologically defined, but one for which we can employ modern molecular approaches. One group of organisms, the cactus breeding Drosophila (fruit flies) of the Sonoran Desert of North America, are ideally suited to studies of adaptation and speciation. Four species of Drosophila are endemic to the Sonoran Desert of North America: D. nigrospiracula, D. mojavensis, D. mettleri, and D. pachea. Each uses the necrotic tissue of a different columnar cactus species as a feeding and breeding site, with the exception of D. mettleri, which breeds in soil beneath a necrotic cactus that has been soaked with necrotic juice.The Sea of Cortez separates the portion of the Sonoran Desert found in Baja California from the part on Mexico's mainland, acting as a barrier to gene flow for many organisms. We utilize molecular markers (Ross et al. 2003; Hurtado et al. 2004) to study the degree to which populations of different Drosophila species from the two sides of the Sea of Cortez exhibit differentiation with respect to genetics. We then measure reproductive isolation at the pre- and post zygotic levels (Reed & Markow 2004), especially assortative fertilization (Markow 1997) to test hypotheses regarding when reproductive isolation appears, and in what form, relative to the earliest stages of genetic differentiation. Cacti have a very different chemical composition compared to the host resources used by most Drosophila species. They are very low in nitrogen and phosphorus (Markow et al. 1999; Jaenike & Markow 2003) and they contain chemicals that are toxic to many species of organisms. Yet the resident Drosophila species can feed and breed in these plants without ill effects. We employ functional genomic approaches, custom microarrays for D. melanogaster and D. mojavensis, to study the genes involved in the utilization of different dietary resources by Drosophila melanogaster (Cartsen et al. 2005) and Drosophila mojavensis (Matzkin et al. 2005). We also study the influence of nutrients on growth rates in Drosophila species that specialize on nutrient-rich versus nutrient-poor food (Watts et al. 2005) |

||||

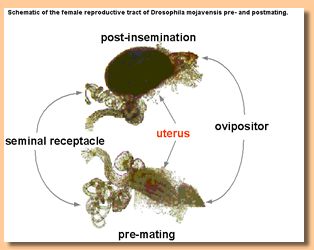

Schematic of the female reproductive tract of Drosophila mojavensis pre-and postmating |

MATING SYSTEM EVOLUTIONSpecies of the genus Drosophila exhibit amazing variability in mating system characters such as age at reproductive maturity, sexual dimorphism in age at reproductive maturity, sperm length, ovariole number, female incorporation of ejaculatory substances, copulation duration, and the presence or absence of male secondary sexual characters (Markow 1996; Markow 2002; Markow and O’Grady 2005). The laboratory is interested in identifying the long-term evolutionary as well as the ecological (Markow et al 2001) factors that underlie this variation. See Powerpoint of sperm length figure for here. |

|||

|

Mechanisms of postcopulatory but prezygotic reproductive isolating mechanisms are likely to be rooted in mating system evolution. Interactions between male and female reproductive molecules and morphology are potentially involved in incompatibilities that occur after mating but before fertilization. Reproductive isolating mechanisms that operate at this level could be due to mismatches between either the morphological (Pitnick et al 2003) or the molecular characteristics (Knowles and Markow 2001) of male and female reproductive tissues. |

||||

DROSOPHILA EVOLUTIONARY GENOMICS

|

Collecting Drosophila from necrotic cardón |

|||

················································································ UC San Diego Division of Biological Sciences Biology Bldg, Room 2212 9500 Gilman Drive 0116 University of California, San Diego La Jolla, CA 92093-0116 Office: (858) 246-0095 Laboratory: (858) 246-0402 Fax: (858) 534-7108 Copyright © 2005-2006, Markow ················································································ Original design by Somi Ruwan Budhagoda |

||||